Cathy Terepocki —

Earth’s Crust

A sense of belonging and a desire to craft meaningful objects that speak about people and places.

by Alieska Robles, Hamaka Creativity Lab

Yarrow, BC cathyterepocki.com

Scientists estimate that 4.5 billion years ago, an asteroid similar in size to Mars hit Earth with immeasurable force and melted the planet to its core, altering its chemical composition. As Earth cooled down, the inner core solidified into a ball of mainly crystallized iron, the middle layer remained viscous, and the outer surface, accounting for less than one percent of our planet’s total mass, hardened into a crust of igneous rocks formed by cooled magma. Water and the first gases of our atmosphere arrived in the meteorites that built the planet, combining with the vapour generated by chemical transformations that condensed in the atmosphere to produce rain and oceans. The new elements of air and water carried particles that accumulated in layers and fused into sedimentary rocks, while heat, pressure, and chemical reactions created metamorphic rocks.

Amidst these changes over billions of years, silicon became the second most abundant element on Earth, after oxygen, and the combination of the two formed silicon dioxide or silica, which accounts for more than 90 percent of the rock components that form Earth’s crust. Over thousands of years, the purest forms of silica-rich rocks underwent weathering, chemical alterations like carbonation, hydration, hydrolysis, or oxidation that are caused by contact with carbon dioxide, water, acid, and oxygen, as well by as the activities of living organisms, the plants and animals that were coming into existence. Through the wizardry of geology and time, fine particles of silica mixed with alumina, water, complementary minerals, and other materials to form clay.

Clay is everywhere. Daniel Rhodes, a ceramic artist and educator, wrote in 1957 in his book Clay and Glazes for the Potter, “More clay is being formed daily than man is able to do ceramics.” What makes it so fascinating, beyond what it is, is what it can become. Shapeless in its natural state, clay has infinite poten-tial in a studio through a potter’s ability to turn a material so widely available into something deeply personal. Working with local clay can also deepen potters’ ties to the land where they live, opening their eyes to the history and geology of a place.

Glaciers melting thousands of years ago in the northwest corner of what we now call Canada shed mineral particles, which clashed against each other while suspended in flowing waterways, grinding finer and finer until they settled near the banks of the Chilliwack River, in the southern part of British Columbia.

The Chilliwack clay deposits caught the attention of construction workers in the 1970s, and they established the first brick factories in the region. In 2017, remnants of abandoned factories and fragments of memory sparked the imagination of Cathy Terepoki, a humble potter looking to connect with her community and the place she called home.

“This is where I live now, and it is important to me to engage with the local community.”

Like clay moving through the water, Cathy’s life exemplifies flow. She grew up in St. Jacobs, Ontario, in a family deeply rooted in tradition. Although her parents didn’t follow the Mennonite customs of her grandparents, Cathy saw the black horse-drawn buggies negotiating the streets, mothers tending gardens, and quilters weaving memories. She re-members running and playing while family members and neighbours chatted and laughed as they sewed scraps of clothing into precious quilts. Pieces of her mother’s wedding dress or her brother’s shirt became part of the cozy blankets that gently enfolded her as she slept. During harvest, cooking and manual labour took the place of the quilting bees; everyone shared farming equipment and filled different roles to help achieve the common goals, which concluded in celebrations of the land’s generous gifts.

The stability of her upbringing gave Cathy the confidence to leave home and experience the world, knowing she would always have a place to return.

She travelled to and fro for six years, visiting Australia, Guatemala, and Indonesia before returning to North America to study and have a family. Along the way, she learned basket weaving, ceramics, harvesting, and other trade skills that funded her travels.

Growing up around handmade objects, and visiting communities abroad with dependable ties to craftsmanship, gave Cathy an appreciation for materials and processes, which led her to a career path that would satisfy her need for tangible experiences. Unaware of the difficulties of living as a maker, she completed a bachelor of fine arts at Alberta College of Art and Design with a major in ceramics and a minor in printmaking, then embarked on a gruelling mission to become a self-supporting artist—which at first involved working 50 to 60 hours per week in her studio while raising her family.

Cathy lived in Calgary, Saskatchewan, and Vancouver before settling in the picturesque town of Yarrow, BC. Casual encounters with strangers often evolved into long-form conversations after she mentioned her pottery experience. Locals soon introduced her to the wild clay in the area and the community’s long history as a brick-manufacturing town; farmers explained the intricacies of growing food in clay-rich soil; excavators shared anecdotes of recent uncoverings.

“We can see and feel without attaching words and concepts to what is around us.”

The recurring comments about local materials inspired Cathy to dig deeper and find the plentiful clay source everyone spoke of so passionately.

She had recently finished an extensive design project, and this gave her the means to take some time off to study the local clay and redefine her future work without worrying about money. Like a treasure hunter, she set out to visit the riverbanks, ravines, and waterfalls near her home, searching for muddy spots and gathering sample chunks.

Most of her trials were unsuccessful until a fortuitous event offered Cathy the secret to a meaningful line of pots and an energizing new obsession. A close friend invited Cathy to a birthday party at a beautiful property by the Chilliwack River. The owners, a couple in their 60s, had a sustainably built home designed by an American architect and made with ground earth, clay slip, and sawdust from the area. They led the way to the ravine and showed Cathy the abundant clay deposits.

The earthy smell of moist soil and pooled rain transported the potter back to her childhood home and reminded her of all the good things that come from the ground, the rich origins of all life on Earth. It made her wonder about the generations of microscopic organisms evolving under our feet, sheltering in Earth’s crust, until that first chance encounter with an inspired potter.

The property owners kindly allowed Cathy to harvest the wild clay as long as she extracted it with care and without heavy machinery that could disrupt the land.

With shovels and buckets, Cathy and her crew walked back and forth amid ferns and mossy trees, carrying the dark grey mud over drenched paths. A natural rhythm guided the process as they filled one bucket at a time, and intriguing conversations turned the laborious task into an intimate collective experience. Many wondered how clay formed and if it was renewable, while Cathy reflected on the fact that science doesn’t have all the answers: “We don’t need to understand everything. We can see and feel without attaching words and concepts to what is around us.”

“It puts things into perspective to think about how long it took for clay to form and be there.”

Before sunset, she returned to her studio with mud caked on her clothing and bare skin, physically exhausted but utterly satisfied. The wild clay wasn’t usable straight from the ground; it had to be tested to identify its properties and melting temperature.

The composition of clay varies based on its origins, but all clay shares two main characteristics: the microscopic size of its constituent particles (smaller than 0.002 mm in diameter), and its affinity for bonding with water, which is responsible for its plasticity when sufficiently wet.

Primary clays remain close to their originating rocks and are typically pure and non-plastic, while secondary clays form when water or other elements carry eroded particles far from their birthing rock, often mixing them with other minerals and impurities. Particle size and distribution can also dictate the clay’s behaviour. Clays with finer particles have more plasticity and shrink more than their coarser counterparts. Potters can combine primary and secondary clays with additional minerals to develop their own clay bodies, making a custom mix based on their requirements for workability, shrinkage, firing temperature, texture, colour, and reaction to glazes.

Cathy has never been keen on facts and technical information, so she didn’t expect to discover the exact scientific composition of her new wild material. Nonetheless, intuition combined with trial and error helped her navigate the limits of the new clay body.

She estimated that adding 10 percent ball clay would increase its plasticity and bring its firing temperature closer to that of stoneware. The process involved crumbling the wild clay into smaller pieces, adding water, and mixing it into a slurry with the additional ball clay. Then, sitting in the sun with the calming hum of the river at a distance, Cathy diligently sieved the mixture to remove grit, rocks, and impurities before pouring it into linen-lined boxes where it rested to dry. Before transforming the dry clay into bowls and mugs, Cathy pressed it through a pug mill to remove any air bubbles and avoid having to wedge the clay and press out excess air by hand. The result led to pots that shrank a little more than those made with commercial clay bodies, but that were easier to shape and more durable once fired.

Many people argued that the arduous process was not justifiable, but where others saw difficulties, Cathy saw an opportunity to prove that obtaining consistent results with wild clay was possible and, ultimately, special.

For the first time in her career, clay didn’t come conveniently packed in a plastic bag. Instead it came full of expectations, fostering a unique connection to place that made it feel cherished. Like a fresh tomato grown with love in the backyard, wild clay is precious and adds a new level of care when working with it. Cathy doesn’t consider herself an emotional person, but she recalls the first time she threw a pot with the local clay as “a profoundly moving experience; the culmination of weeks of work harvesting and processing.”

The high demand for commercially mined clay continues to rise. However, if more potters looked beyond the ready-to-use clay bags and harvested local clay using non-damaging techniques, as Cathy has done, they could reduce the amount of mined clay travelling in trucks worldwide.

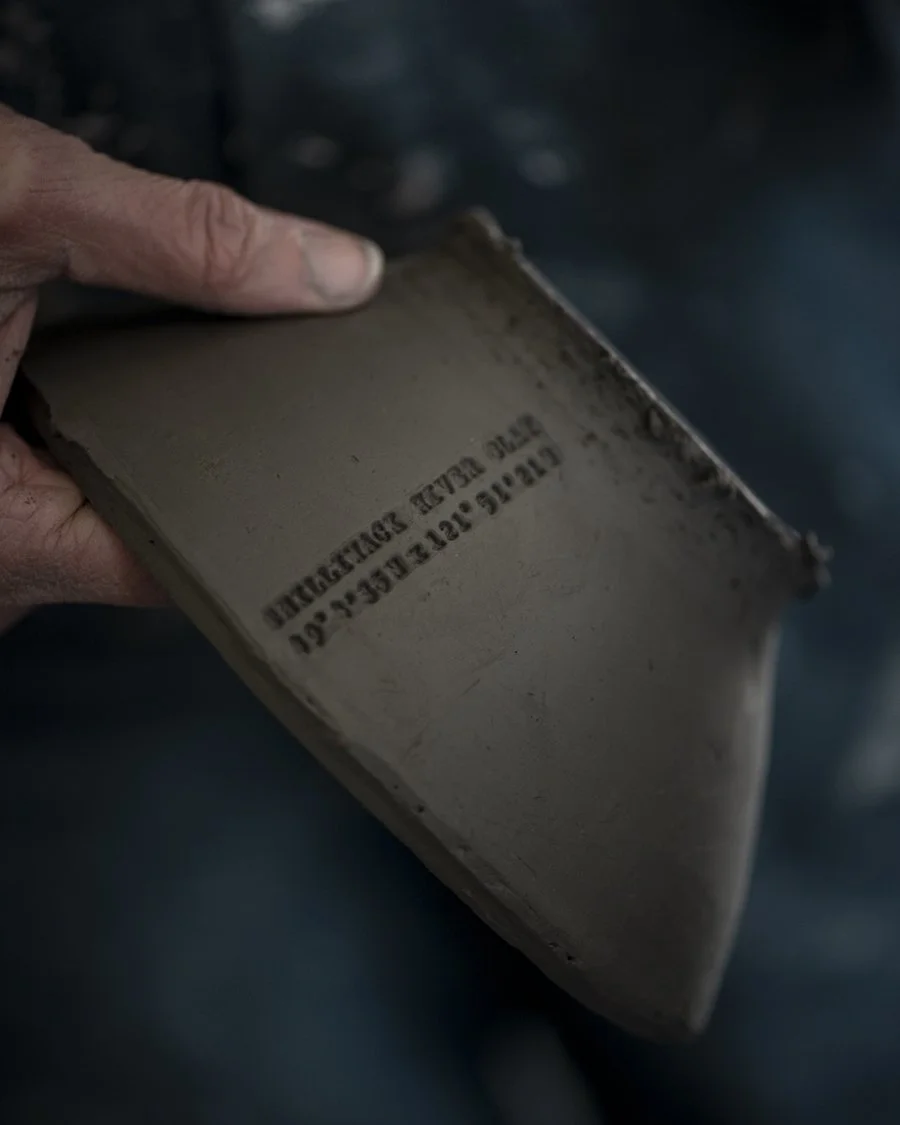

To keep her new work affordable for others and sustainable for her studio, Cathy had to be practical and compromise on form and surface treatment. Her previous work boasted overlapping colours and patterns, but the wild clay pots decorate themselves with a heartwarming toasty colour once fired. She often visits the river to collect rocks and landscape images that inspire the colour palette for her glazes. And it felt appropriate to stamp the objects with the coordinates of the river—a simple yet powerful statement that awoke a distant memory of her time working at a gold mine in Australia, where she gathered samples and stored them in canvas bags marked with the coordinates of their extraction.

Geology, chemistry, art, history, and psychology come together in perfect synchrony for Cathy. “Clay is a natural material that took millions of years to form, and once it’s bisque fired, it will take another million years to fuse back into earth. It puts things into perspective to think about how long it took for clay to form and be there. It is humbling and makes you feel small in the vast scheme of things.”

With this perspective, Cathy focuses on sharing meaningful stories through her work instead of merely adding more things to the overwhelmingly growing ceramics market. “People are usually content to buy handmade and pretty, but most people don’t dig deeper and inquire about the maker’s process. It’s the same as buying organic food from the grocery store instead of getting to know your farmers and how they grow your food.” She shifted the conversation from aesthetics to people and place, with a proud sense of belonging, respect, and responsibility for Chilliwack and her fellow city dwellers.

Cathy now realizes how her life circumstances and her travels informed and shaped her work over time. “Inspiration comes from a melting pot of years of exposure that eventually collide and produce something that feels right.” A maker’s best way to show appreciation is to work with gratitude, responsibility, and kindness for people and places. In Cathy’s words, “This is where I live now, and it is important to me to engage with the local community and create work with meaning.”

“When you take from the ground, it makes sense to give back.”

During her upbringing, Cathy saw families sharing 10 percent of what they made with others. Memories from her childhood in a Mennonite community inspired her to follow the same principle with her new work and give back to the community, especially to wild conservation initiatives like Wild Salmon Defenders Alliance. “When you take from the ground, it makes sense to give back.”